High rise firefighting: From practical to tactical with Brent Brooks

- March 3, 2023

- 8:30 am

Iain Hoey

Share this content

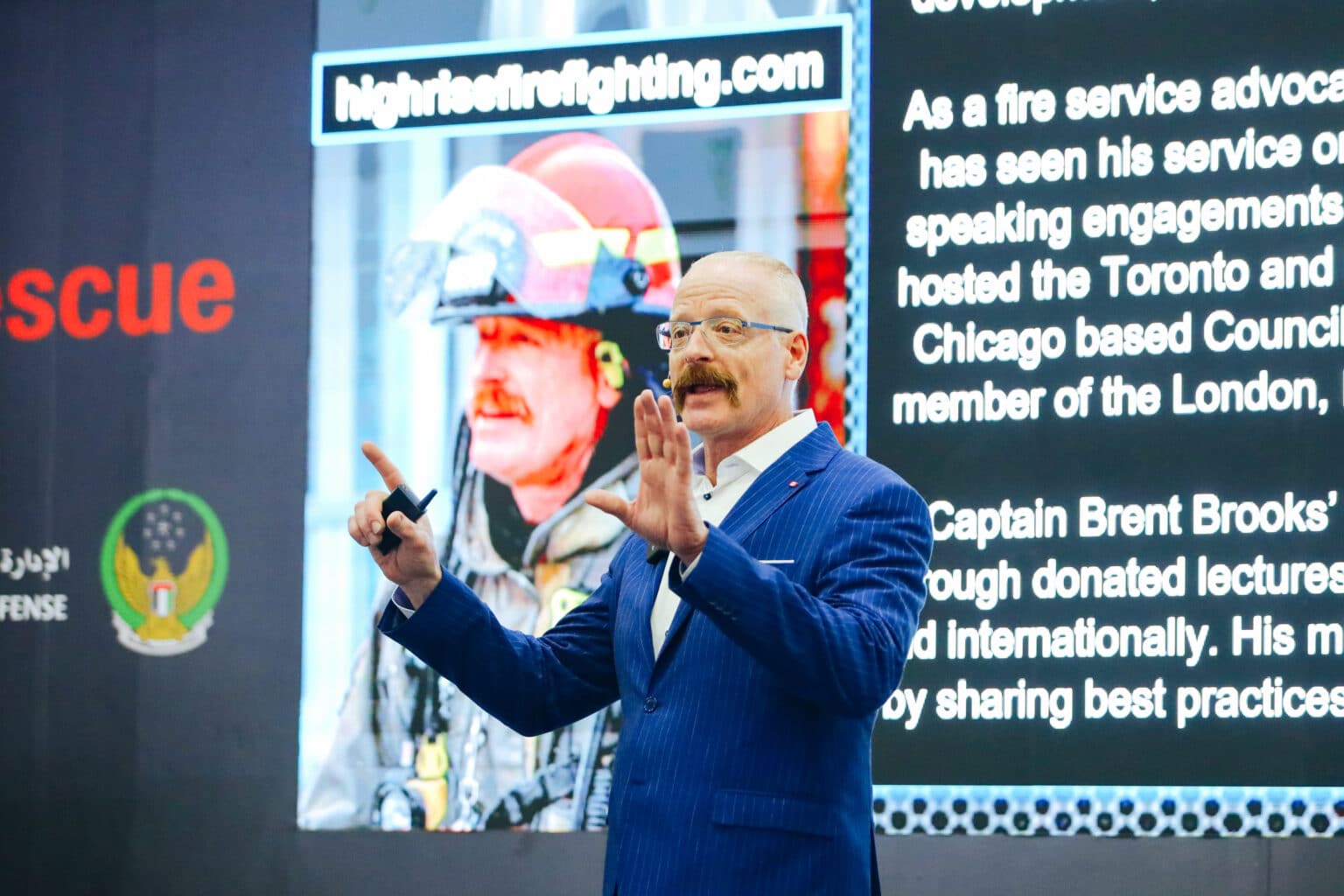

Brent Brooks, Specialist at HighRise Firefighting, considers the high rise challenge

High rise fires have been a growing issue around the world, and with cities continuing to build upwards it is inevitable that this is a scenario firefighting teams will be faced with over and over. In every tragedy, there is a lesson to be learned, which is why Brent Brooks, acting Captain with Toronto Fire Services, has made it his mission to understand the challenges of high rise firefighting to ensure that, whenever the next tragedy strikes, firefighting teams will be prepared for every outcome.

Brooks spoke at Intersec 2023 Fire & Rescue Conference, hosted by the Directorate General of Dubai Civil Defense, to talk about developing a tactical approach to high rise firefighting and minimising loss of life.

Background

“I am a boots on the ground firefighter,” opened Brooks, “I could be going into a high rise fire every single time I go into work.” This is certainly no exaggeration. Brooks is part of High-Rise Unit 332 in Toronto, Canada, and he noted that the unit get called to around 16 fires a day. The number of calls in the city was so high that there was the need to add a second high rise unit and are expecting add two more high rise units in the near future.

In 2010, Brooks and his team attended an incident that caused a career pivot and saw him refocus his energy towards researching high rise firefighting: “If you get to a point in your career, regardless of what your career is, and you think you know it all – it’s time for a reality check. You’ll never know everything you need to know about your topic.”

He spoke about the six-alarm fire at a high rise building that changed his career: “It was my crew that had the mayday. We almost lost two firefighters lives that had to be rescued. The other firefighters were burned very badly. This fire burned for eight hours. It was contained to a room and contents – how can that burn for eight hours?”

This question drove Brooks down the rabbit hole of research, vowing to understand the nature of high-rise fires to ensure that this would never happen again. He listened back to the audio recorded during the fire and found that their response was ‘absolutely textbook’: “There was nothing we did wrong, we followed the policies and procedures. We accepted that.

“In the investigation following the fire, they said that ‘this is high rise firefighting, its wind impacted, it is going to be difficult’. I still wasn’t ok with that.”

On the job research

At 650 parliament street, Toronto, the team faced had two fires in under a year. The building’s inner workings were burned from the bottom right through to the top: “There was nothing we could have done about it. We gathered every single 100-pound CO2 extinguisher city wide and brought it to the fire. We can learn from this.”

In another incident where Brooks and his team were first on the scene, they actioned the flow rates that Brooks had been researching: “It proved to us that big water matters. Our flow rates matter. What we’re putting on the fire really matters. We made really quick work of this fire.”

In 2018, the team had realised the value of staging resources inside the building in the event of emergency – and that’s exactly what happened when they were able to use equipment that they had previously positioned at the location of the fire: “There was a firefighter mayday, the firefighter went down, our team were in position and we were able to rescue this captains life because we were in position to be proactive, not reactive.”

At another alarm in 2019 at the building that sparked Brooks’ focus, they learned about pressure isolation and keeping the smoke contained to the fire floor. “We also learned door control – that is a big thing when you look at high rise buildings with the compartmentalisation. Door control is key.”

Brooks added that he was at the Tall Buildings Conference where he learned about vertical metal cladding: “This is the future. We did the research, the science and the investigation into this. We know what fire does. We know the megawatts that the fire puts out – and how many litres per minute we need to put on that fire to put it out. The science and math are correct.”

A new approach

When looking at his unit’s tactics, he went to the city planning department and asked for history of the city of Toronto. The gist was that firefighting tactics have been designed around 1960s-70s building types, but that this does not account for new building structures developed in the intervening years.

“These are all a lot more complicated than the 1960s buildings that our high rise firefighting tactics are built around. We have high rises, wide rise, vertical village, horizontal high rise, high rise buildings on its side, ground scraper, ply-rised and tooth picked towers.”

With this in mind, he says the idea, he says, is to develop a tactic for every scenario and not be caught out or delayed by not having the right equipment or taking the wrong approach.

Part of this tactical planning involved timing: “We started timing every single thing that we do in Toronto, we know how long takes us to get to any building address – but we don’t know how long it took to get to the true fire location. It takes us longer to get from parking the truck to the fire.”

Brooks noted that there is an NFPA standard of two minutes to get out of the fire station: “There’s another four minutes to get to the call. That’s six minutes to get to the building address. It takes a further six minutes to get to our alarm location. We have to enter the building and do our investigation – this is taking 12 minutes after we arrive to get water on the fire.

“During that 12 minutes we have to start setting the stage for our vertical response: figure out the ventilation profile of the building, wet-test the Fire Department Connection, I need to begin staging equipment then here is the difficult decision – are we going to shelter in place, evacuate, or are we going to defer this? We can predict and forecast what that 12 minutes is going to look like in our city. High rise fires are predictable now.”

He said that his team’s Plan A is to use the building’s fire model, Plan B is using the fire truck pumping in from the department connection. If A and B fail, they are going to run a line into the ground floor stand pipe and if it will accept it. If they all fail, Brooks’ unit has eight different tactical options for the crew that went up: “There’s no added equipment that has to go along. We also started staging equipment – we’re being proactive, not reactive.”

He added: “We can predict what’s going to happen with a fire in the next 12 minutes, so we can know if a fire is going to the roof and be prepared for that. We’re ready for the effect for wind, door control, we are getting better and better, but it takes research.

“The point is being ready for anything and knowing how fire works. We have tactics for everything. We did all this research, putting the science into high rise firefighting, but it takes your feedback to help me.”

This article was originally published in the January edition of IFSJ. To read your FREE digital copy, click here.